Two weeks ago, the first Manchester Arena Inquiry report was published. The report contained a detailed investigation into the failings surrounding this tragic attack in 2017 and included recommendations for counter terrorism. The report also commended the ‘Protect Duty’ as a huge step in the right direction for the protection of people when attending events and public spaces.

We examine the main recommendations and the implications that these might have on today’s security industry.

Vigilance must not wain, empowerment is key:

One of the first conclusions from the report was that inadequate attention was paid to the threat level which had been ‘severe’ at the time of the Ariana Grande attack. It was thought that the prolonged period that the threat level had remained at ‘severe’ had desensitised security teams. This is not to say that the threat level was not right to remain at ‘severe’ for the time that it did but, that more credence should be paid to the threat level published. Operational procedures should have altered in line with the severity of the threat. It is vital that vigilance is maintained and does not wain during an extended time of being at high risk of an attack.

Robust procedures and awareness of these should have a waterfall effect on stakeholders. Operational protocol and perception of risk should be instilled from the top down, to include building owners, lessees, employees, government entities and anyone else with a part to play such as a security subcontractor or supplier. For instance, any suspected threat raised or reported should be followed up by security personnel and the police until proven to not be a threat or of any concern by the authorities. Employees should feel empowered to be able to do this without the fear of causing disruption or creating false alarms at the detriment of a live event. There will be false alarms, this will be part of the course.

Safety & security should be collaborative for maximum effect:

Mandating owners of public spaces and venues is complicated due to multiple stakeholders and not one with a clear responsibility or remit for security. The subject of a ‘Protect Duty’ will be owners of land or occupiers, occupiers or the head lessee. Where separate venues such as shops/bars or stalls are occupied by different leaseholders within one master building owned by a head lessee, this further complicates matters. If the overall responsibility for security is then subcontracted out to a supplier, the responsibility for security then falls within the supplier’s remit. Would that then mean that security subcontractors and suppliers are subjected to a Protect Duty? When responsibility for one area ends, who then picks up the external area – the police force? The answer to this complicated mix is that if multiple stakeholders exist at a venue, all are responsible for the safety and security of employees and visitors attending that venue. Not one area is outside the jurisdiction of one stakeholder.

For security to be effective and for mistakes not to slip through the net between stakeholders, all parties must be identified and must work together by committee to be aware of all advice and recommendations regarding the addressment of risks and ensuring that security protocol is successfully implemented and followed.

The Protect Duty aims to provide a framework and reinforce the need for constant vigilance and review to guide stakeholders. A common-sense approach is needed here. Responsibilities will be addressed collaboratively by legislation, as commercial pressures may prevent this being achieved voluntarily. Looking at venues such as the Manchester Arena, a high standard of protective security is justified as the consequences of an attack are more serious. The venue itself is also likely to have greater resources to put measures in place.

Do planning regulations have a part to play?

Eliminating or mitigating the effect of a terrorist attack should be part of the pre-building process. It is much easier to insist that measures are included within a new build structure than it is to retrofit into an existing buildings fabric. New build or change of use applications should assess the suitability of design and materials for providing the level of security required and addressing potential vulnerabilities.

Most authorities outside of the City of London and Westminster do not currently consider conditions related to terrorism mitigation. Bodies such as ‘Secure by Design’ are consulted to address criminality concerns. A certified security expert is also requested to be commissioned by applicants to produce a ‘crime impact statement’ which considers factors such as crime statistics, building layout implications and material/product recommendations. No compliance or enforcement is assigned to the document however as product specification and details are beyond the remit of planning considerations.

It is difficult to see how this will be addressed within the current planning and building regulations structure. The exact part that planning regulations must play in the future will become clearer in time when the ‘Protect Duty’ forms part of government legislation.

How can the ‘Licensing Act 2003’ be utilised to tackle terrorism?

Under the Licensing Act 2003, Council’s like Manchester City Council act as the licensing authority, taking responsible for alcohol licensing as well as regulated entertainment and late-night refreshment. As the licensing authority, activities are governed by the promotion of four licensing objectives:

- The prevention of crime and disorder

- Public safety

- The prevention of public nuisance

- The protection of children from harm

The ‘Licensing Act 2003’ already considers public safety. It was advised within the first inquiry report that an addition to current guidance is made which is consistent with the new ‘Protect Duty’ to provide guidance for venues and business owners.

There is certainly a balance to establish as, doing nothing is not an option, but being overly prescriptive will interfere with enjoyment.

Implementation of the Protect Duty should be ‘reasonably practicable’ and proportionate. The term ‘reasonably practicable’ is well established in health and safety policy and encourages “weighing a risk against the trouble, time and money needed to control it.” ‘Security’ however is a new concept and one which requires further determination and legislation by government.

Other matters dealing with public safety such as food hygiene is rigorous and so there is no reason why the introduction of the Protect Duty would not also be rigorous. There is no evidence to support that terrorism threats are short lived. There is however evidence that threats and attack methodology changes, therefore a robust vulnerability assessment and risk analysis should feature as part of the Protect Duty legislation.

Proposed framework for the Protect Duty:

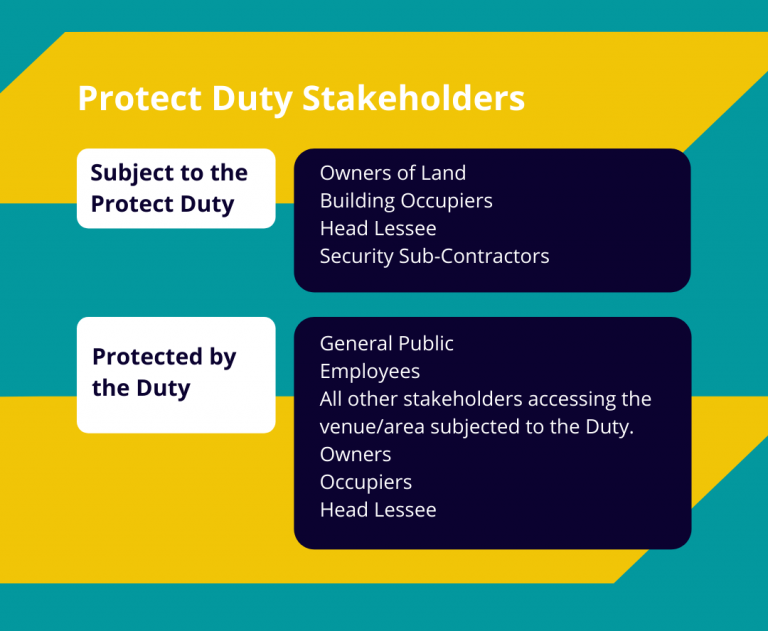

The Protect Duty has been designed to protect stakeholders operating within a publicly accessible area (paid entry or otherwise) and within commercial organisations housing over 250 people at any one time. The stakeholders affected are as follows:

The exact mechanism of the Protect Duty is for government to decide however, the first report did release some guidance on a possible framework to be included within the Protect Duty to guide and inform those affected:

The aim of the initial risk assessment is to produce a ‘Protect Plan’ which includes control measures for assessment and review. The risk assessment will identify potential vulnerabilities and weak points within a venue’s protective security measures and procedures. If the threat to these vulnerabilities identified is deemed realistic, this will leave stakeholders with a ‘residual risk’ which will need to be addressed through mitigation and an action plan. An audit would then need to be commissioned to certify the actions taken and, a further stage for enforcement following an audit failure is also suggested.

The ‘Licensing Act 2003’ subjects a venue to planned and unplanned audit visits. There was a recommendation that these audits would extend to cover elements of the Protect Duty too as part of the audit and review stage.

Considerations for the implementation of a Protect Duty framework:

One of the concerns when implementing any form of risk assessment or audit is the consistency of approach. Any risk assessments must be underpinned by a kitemark of approval to indicate a quality benchmark. Assessment must include regular criteria to produce a competent report with consistencies depending on the size and type of venue. A review process must be robust and at regular intervals to consider changes in threat landscape and the technology available to mitigate threat.

In the case of the Manchester Arena attack, active enforcement, or the lack of resulted in breaches which were not picked up due to insufficient resources. Counter Terror Security Advisor’s (CTSA’s), licensing officers, police licensing enforcement officers and the Security Industry Authority (SIA) could join forces here to address the failings.

Failure of other schemes implemented over the years has been due to their voluntary nature. Enforcement consequences should be as serious as the current consequences of a health and safety breach in legislation. Inspections should be both planned and unplanned, visits can be tailored to also accommodate licensing checks to maximise resources.

Training of stakeholders subjected to the Duty is imperative. ACT training is offered free and has been set-up and delivered by NaCTSO. More targeted and specific training for employees or positions responsible for safety and security should be adopted where relevant, the SIA can provide some of this.

E-learning courses and modules alone were recommended to be not sufficient, even if the course is deemed high quality. The limitations of E-Learning needs to be recognised and further ‘on-the-job’ training tackled with security personnel. Prevent and respond training to include first aid to equip security personnel to also handle first response support should a terrorist incident occur. NaCTSO have many central training and information documents, these were recommended to be utilised more in a central library set-up with planned and secured access to ensure that information does not fall into the wrong hands.

All those who operate and monitor CCTV should be operating under a SIA CCTV operator’s license which involves the necessary training. This to apply to in-house and external personnel.

Companies who provide security services should be licensed. The SIA have an ACS (approved contractor scheme) which would ensure that only fit and proper companies would be able to carry out the work.

Savings must not be made at the cost of safety. Security measures are expensive but, not as costly as cutting corners and suffering the consequences.

Summary of the main recommendations:

Further expansions on things such as the definition of ‘security’ could help to inform legislation further but, is most probably too much detail for this overview.

The four main outcomes of the initial Manchester Arena Inquiry Report are:

- A framework is required to guide compliance

- Stakeholder collaboration is critical to success and the prevention of security breaches

- Employee training and empowerment is crucial to tackle on the ground security and first response should an incident occur

- Review and enforcement should be a regular cycle to promote improvement and awareness of shifting threat landscapes.

One single entity can not tackle the implementation of the ‘Protect Duty’ alone, third parties such as the police, SIA, NaCTSO, local authorities, planning bodies and CPNI must all play a role as the transition evolves into legislation.

If you’re currently working on a physical security scheme and need help, contact us.